By Simon Pentanu

Every picture tells a story. Every story a picture tells may not be a perfect story but, as another saying goes, there’s more to the picture than meets the eye.

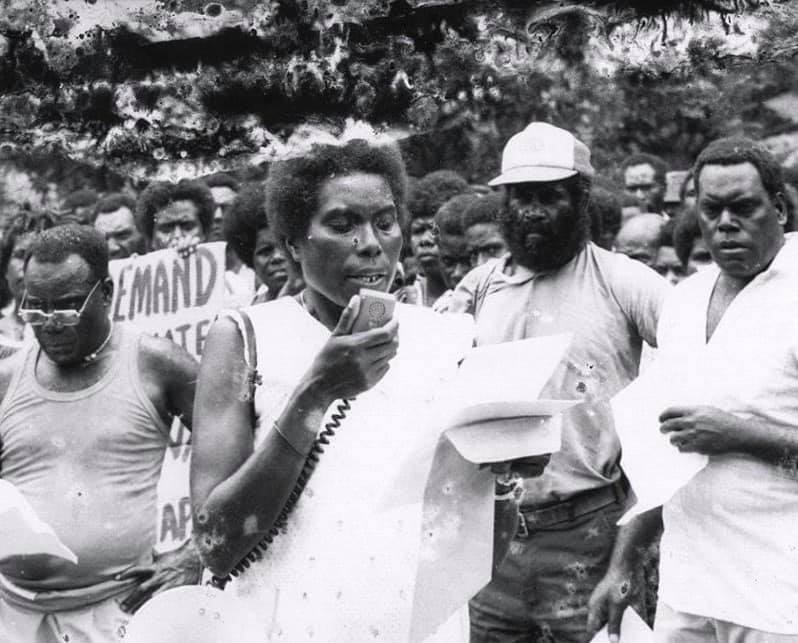

There is a certain poignancy about this picture – and many other images connected with the multitude of matters surrounding Panguna.

Panguna is not merely a history of mining, minerals, money, maiming and the nastiness of the conflict. It is not only a story of lost lives, lost land and lost opportunities.

Panguna is a story of many individuals and groups; of men, women and children of the forest, the valleys, the ravines, the hills and mountains, the rivers and creeks, the sacred sites – all of which people called home, before mining arrived.

Perpetua Serero and Francis Ona both passed away relatively young. The effervescent Damien Dameng – the one with reading glasses studying his notes in this photo – lost his life under dubious circumstances only in recent times.

Francis Bitanuma with the white cap and overgrown beard in this photo, is still around, raising his voice and picking and choosing his fights but with fewer and fewer local allies in tow.

Perpetua Serero had remarkable poise and presence. Had her voice as Chairlady of a splinter Panguna Landowners Association (PLOA) been heeded when she spoke (either with or without the aid of a hand-held loud hailer), some of the fiasco and hurt amongst the landowners could well have been mitigated, if not largely avoided.

Instead, the very early feuds over Panguna over benefits accruing from the land under various leases to BCL were between landowners themselves. Only a dishonest landowner would deny this was the case.

Disputes and differences over land sharing, land use and land tenure preceded the arrival of mining in Panguna. But these were localized and tended to be confined within households, extended families and clans. Agreements were brokered to resolve issues or at least keep them to manageable levels. There were ways for everyone to move on, living and communally sharing the land, rivers, creeks, the environment and everything that more or less made life worth living and dying for.

Differences and feuds over the benefits accruing from the mine such as RMTL (Road Mining Tailings Lease) payments, invonvenience payments, and other payments added fuel to existing disputes between clans, families and relatives. Some of the disputes became vexatious with the advent of mining.

Mining catapulted Panguna women like Perpetua Serero, Cecilia Gemel and others to the forefront as they took on much more active and pronounced roles as mothers of the land in a society that is largely matrilineal.

This photograph shows a woman, leading her male counterparts in the early days of the dispute involving one group of Panguna landowners voicing, in a very public way, early warnings of what might follow.

The significance of her message was either lost to or not taken seriously by most leaders from central Bougainville, BCL, PLOA and relevant authorities in the national Government at the time.

That men are on the periphery in this photo – in stark contrast to the lead role being played by Serero at the front – wasn’t just symbolic. It was real. Her position at the front, with the support of men such as Francis Bitanuma, Francis Ona, Damien Dameng and others was neither incidental, coincidental nor accidental. Her role at the forefront of this dispute over land was natural and logical, because in most of Bougainville it is through the women that land is inherited and passed down the generations.

That more and more landowners became willing to front up in crowds such as this, emboldened by the willing maternal leadership of someone who stood up to carry the mantle of those that bore grievances against their own PLOA, led by men. Serero, and the landowners who stood with her, made a brave and significant statement.

As the differences grew, the younger Panguna generation – alongside women like Serero and Gemel and the emerging, vociferous Francis Ona – turned their attention to Rio and BCL.

Increasingly they saw BCL and the old PLOA as having all the control and influence over what happened in special mining lease (SML) area. The injustice felt in not having much say weighed heavily and became a rallying point as captured in this photo.

All of us observing, reading and writing about the upheavals over Panguna, the mounting dissatisfaction, the criticism of the Bougainville Copper Agreement (BCA) and the rebellious response that shut down the giant mining operations, may find some satisfaction in the common truism that hindsight is a wonderful thing.

The BCA was a document familiar mostly to lawyers, investors and bankers and, of course, to the mining fraternity. It was not until well after the first power pylons fell, after deployment of the security forces and after the mine was closed that interest increase in reading the fine print of the BCA.

Coming, as they did, from a paperless village life, many landowners and Bougainvilleans in the community at large found little compulsion to read, let alone understand and appreciate legal agreements.

When the going was good everything was hunky dory. The landowners were getting their lease payments, social inconvenience compensations, royalties etc. The provincial government was doing well and was financially better placed than others in the country. Employees couldn’t really complain about the job opportunities, good salaries and wages. Their disposable income was far better than the public servant who also had to cope with overheads.

The majority of the landowners the BCA was purported to serve turned against it, despised and rebelled against it.

It is a story new generation of Panguna landowners is born into. It is not a story restricted to past or the future. Rather, it is a story that evokes timeless lessons and has some relevance for all of us forever throughout our lifetime.

It is true, hindsight is a wonderful thing.

I have heard a lot about Perpetua Serero. I never met her. I will never meet her in person because she has passed on.

She served her calling with tremendous support from men and women of the land. She had faith in customs and traditions that gave equal opportunities to women. These customs and traditions gave her the mantle and legitimacy to lead protests against the male dominated RMTL executives in the Panguna Landowners Association.

She faced an awful amount of pressure because of intense feuding over control of PLOA and RMTL in Panguna. She took the baton and ran her lap hoping to influence and change some of the male dominated status quo in the old PLOA.

The Australian Liberal and Labor colonial governments clearly saw what was going on and regarded Panguna mine as a future investment to finance a future, independent PNG. It turned out that any mining, unless the traditional land tenure is understood would be the Achilles of mining investment in Panguna, and indeed as it has turned out, in the rest of the country.

Men like Ona, Bitanuma, Dameng and women like Serero, Gemel and others gradually realised that unless they stood up and were counted, taking a stand against the inequities they saw, they would be swamped and inundated by the complacency that was prevalent, accepted, and that supported a Panguna that seemed all normal driven by profits and benefits of mining.

There are lessons Rio and BCL learnt out of the land dispute. Some of these lessons are harsh. Some even the best legal agreements cannot address, avert or fix, for they are based in customs and culture, not common law.

Panguna may be most uncommon dispute or problem of its time that a foreign mining company has had to face and deal with. Its repercussions and reverberations spread through Bougainville and indeed around the world very quickly. It has unearthed lessons that go well beyond issues normally associated with mining.

The Bel Kol approach initiated by the landowners shows traditional societies also have ways, means and mechanisms by which to resolve seemingly intractable disputes. These ways are local, restorative and win-win in their approach, not adversarial, competitive and foreign.

Some of the continuing pain, ill effects and trauma over lost land and lost dignity over Panguna are more destabilizing and debilitating than the crisis and conflict that landowners and many other Bougainvilleans endured.

Everyone that has lived through the crisis on the Island or has been affected one way or another, directly or indirectly, has had to deal with the horrors of crisis, war and conflict. Rebuilding lives, normalcy and returning to a resilient society is a longer journey that will take many generations over many lifetimes.

Little wonder people are prepared to protect their rights and defend the land with their lives. It is true, isn’t it, that one cannot fully understand and appreciate peace and freedom unless you either lose it or you have been suppressed.

I hope looking back we can pass on to the next generation the genuine benefits of hindsight.